Study finds Tibetan Mastiff wolf-hybridised to survive

Recent study suggests that in the distant past, Tibetan mastiffs (as a domestic dog type of breed) could survive in harsh, low-oxygen high mountains' environment thanks to being randomly hybridised with mountain wolf individuals (vide Tibetan wolf), by gaining hypoxia tolerance.

Some time ago, certain photo re-appeared - an endangered[1] Himalayan wolf species female being mated by a free-ranging domestic dog. The photo comes from the Field report led by Lauren Hennelly in Spiti Valley, India, dated 2015.

Notice: Himalayan wolf [Canis himalayensis] is genus Canis representative, where the gray wolf [Canis lupus] species belongs as well. Its taxonomic status - of being a gray wolf subspecies - stays under discussion.

That's nothing new - an international study published last year confirmed that approximately 60% of Eurasian grey wolf genomes carries domestic dog marked DNA on their gray wolf gene pool, which suggests wolf-dog cross-bred geographically widespread in Eurasia for hundreds of years (confirmed as less frequent phenomenon in North America).

Despite the evidence of hybridisation among Eurasian grey wolves, the wolf populations have remained genetically distinct from dogs, suggesting that such cross-breeding does not diminish distinctiveness of the wolf gene pool if it occurs at low levels.[2]

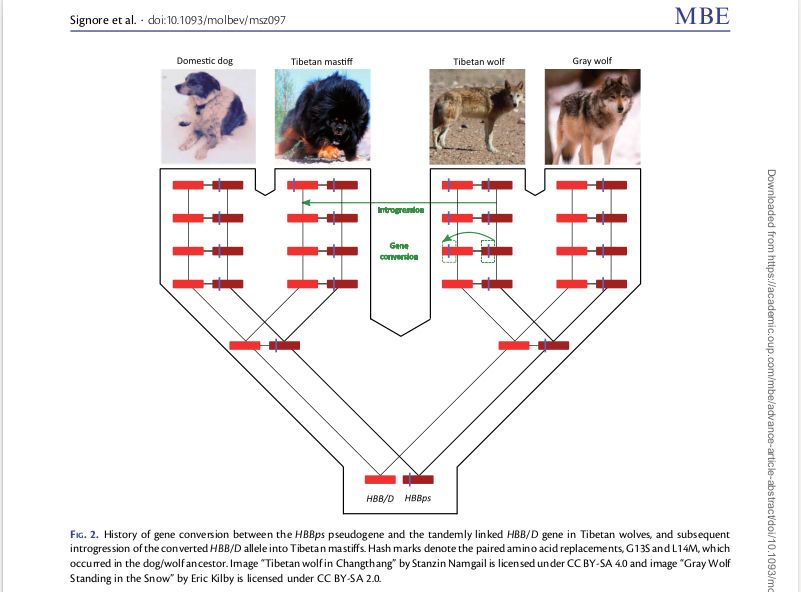

Recent study - supervised by the Lincoln’s University of Nebraska, in collaboration with Qinghai University in China - suggests that in the distant past, Tibetan mastiffs (as a domestic dog type of breed) could survive in harsh, low-oxygen high mountains' environment thanks to being randomly hybridised with mountain wolf individuals (vide Tibetan wolf), by gaining hypoxia tolerance.

Notice: Tibetan wolf [Canis lupus laniger] is a gray wolf [Canis lupus] subspecies (Eurasian wolf [Canis lupus lupus] precisely), genetically Himalayan wolf [Canis himalayensis] similar (ecological niche), rooted to Holarctic gray wolf originally (wolf migrations).

It is the first study showing that an evolutionary adaptive gene mutation (two amino-acid tweaks altered) of the high-altitude species were selectively introgressed into another one.

The research results stand that Tibetan mastiff’s hemoglobin - the iron-containing protein carrying oxygen in blood - architecture absorbs-releases oxygen circa 50% more efficiently than in case of other dog breeds (absent in also researched samples - half-Great Pyrenees and half-Irish wolfhound), especially under thin-air conditions. It hypothesises that an inactive dual mutation, laying dormant in the wolf subspecies genotyp, was passed into the corresponding segment of a similar active gene in the domestic mustiff's one.

There had been no direct evidence documenting that, yes, these two unique mutations have some beneficial physiological effect that is likely to be adaptive at high altitude.

— Jay Storz says, professor of biological sciences, the research leader.[3]

What we’ve discovered is one of the reasons why the Tibetan mastiff is so different from other dogs. And that’s because it’s borrowed a few things from Tibetan wolves.

Tibetan mustiff is a Molosser - large type - dog, historically bred to herd flocks in Tibet and protect sheep grazing on pastures from predatory attacks taking place up to 4000-5000 metres above sea level, where local wolves were apex. Those are heights which no other dog breed - or an average free-ranging dog - is not able to survive.

In the inheritance context, it puts hybridity process under reconsideration - is it indeed a one-sided, negative process.

Both, local Himalayan wolf population and Tibetan wolves, naturally inhabit Tibet - dispersed within the Tibetan Plateau territory (therein Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and partial Himalayas), still independent genetically unaffected by domestic dog's instinctively human-associated nature.

references:

Himalayan wolf and feral dog displaying mating behaviour in Spiti Valley, India, and potential conservation threats from sympatric feral dogs (2015); Lauren Hennelly, Bilal Habib, Salvador Lyngdoh (Department of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Wildlife Institute of India)

A new macroecological pattern: The latitudinal gradient in species range shape (2018); research by group work

Adaptive Changes in Hemoglobin Function in High-Altitude Tibetan Canids Were Derived via Gene Conversion and Introgression (2019); research by group work

[1] Himalayan wolf population counts 350 (1995) for Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh as its natural habitat. Officially listed as protected by Schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act 1972.

[2] citation after ScienceDaily (March 21st, 2018) via "New genetic research shows extent of cross-breeding between wild wolves and domestic dogs"

[3] citations after University of Nebraska–Lincoln (Nebraska Today; Sep.4th, 2019) via "Wolf hack: Study details how Tibetan dog got oxygen boost"