Wolf in Japan

Shinto wolf is related to mountains, mountain tops and cordilleras. It identifies a mountain guardian helping travellers by guiding them if lost (Jap. 送り狼, okuri-ôkami, 'sending wolf').

The first connotation which comes to my mind when I think about Japan is a specific contrast and balance - both such opposite as inseparable, completing each other, seemingly contrary sides. The past and the future, archaic and futuristic, tradition and technology, folklore and pop-culture - shaping Nippon same historically as ethnologically.

Traditional religion which stays consistently dominant in Japanese country, is Shintō (神道, also called 'kami-no-michi' ['way of the gods'])[1], folk Shinto to be strict - an ethnic belief in multitude of gods/spirits (referred as 'kami'), divided between shrines dedicated to a different kami each, although celebrating similar rituals, ceremonies, festivals (matsuri). Character of kami seems to be dualistic - split into material form (every biotop, fauna and flora representative, man-made artefact, human hero, ability, natural or supernatural phenomenon) and spiritual one (emblems, amulets, saints, passed souls). Before Edo jidai (江戸時代) as Medieval equivalent for similar period in Japanese chronology, there was Ko-Shintō (古神道) in Jōmon jidai - associated with an original ancient animism, on which Ainu core religion is based. Kamui are equivalent to kami in Ainu lore, additionally hierarchic, plainly split into positive and negative.

Ainu (アイヌ, also Ezo (蝦夷)) are indigenous people of Hokkaido island. Their ancestors reached Sakhalin, Kuril Islands (currently both being a part of Russian territory) and the Japanese archipelago more than 6 thousand years ago as a hunter-gatherer, fishing people crossing from Asia.[2] Ainu culture is supposed to originate from a merger of other cultures like Okhotsk one, post-Jōmon Satsumon Bunka (擦文文化) and most of all Jōmon jidai (縄文時代) itself as Neolit equivalent for similar period in Japanese chronology. Coetaneous Ainu, living on Hokkaido by generations, are ethnic minority assimilated with the rest of autochthonic Japanese population almost completely. Among remaining dozens of thousands, barely few hundred kept their cutural independence.

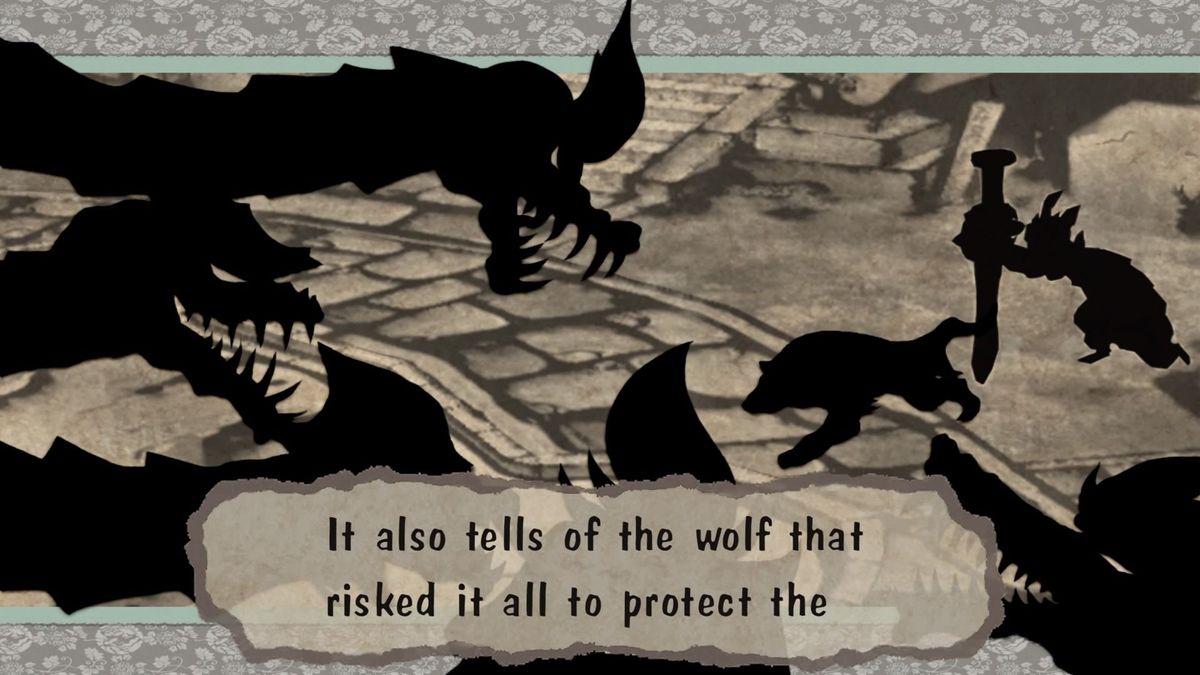

Indigenous Ainu people believed that their ancestors were born from a wolf-like creature and a goddess. Ōkami (Jap. 大神) means literally "great god", "great spirit", or "wolf" if written as 狼. Shinto wolf is related to mountains, mountain tops and cordilleras. It identifies a mountain guardian helping travellers by guiding them if lost (Jap. 送り狼, okuri-ôkami, 'sending wolf'). In Shinto way, farmers stayed aware of wolf protection of the rice fields against boars, deer or hares - potential prey in wildlife. Predators supposed to help to control potential losses. Currently, both Japanese wolf species are extinct.

- Canis lupus hattai (Jap. 蝦夷狼, Ezo Ōkami, 'Hokkaido wolf', 'Sakhalin wolf' in Russia) - extinct probably in 1889, was a relative of North America/Canada wolves (i.e. British Columbia wolf), not Eurasian ones.[3] 'Ezo' historically refers to Ainu whose same-named island has been called Hokkaido since 1869. Autochthonic Ainu treated wolves the same way as domestic dogs by mating them freely and allowing their hybrid offspring to roam on wolf-inhabited areas.

- Canis lupus hodophilax (Jap. 日本狼, Nihon ōkami, 'Japanese wolf') - listed as extinct in 1905. Its natural habitat were mountains of Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku islands. Small (close to coyote) size and visually dog-like look put that animal under discussion on its Canis lupus origin. The term "mountain dog" (Jap. 山犬, yama inu) is commonly used to describe Japanese wolf. It was proclaimed to be a local relict grey wolf subspecies, a primitive form which survived in isolation. Research on DNA analysis of samples taken from various areas of Japan confirmed that Nihon ōkami was Eurasian wolf subspecies from the continent.[4] It's considered that some of them migrated to Japan from the Korean Peninsula during the glacial period and stayed cut off from their continental fellows after the sea levels rose because of the earth global warming. Another study indicated that 28 thousand-years-old wolf remnants from the Yana River (Arctic Siberia, the northern coast) share common ancestry with the Japanese wolf.[5]

Theories of both wolf species of Japan extinction are still disputable. Starting from 1732 (Jap. 江戸時代, Edo jidai), rabies consistently decimated their enclosed populations. Animal disease symptoms (aggression, sudden attacks) were a factor - a reason why 'Yama inu' became a synonym of rabid dog. The next period (Jap. 明治時代, Meiji-jidai) came upon them almost completely extinct. It was a time of fundamental changes - modernization, foreign relations, firearm implementation. Native predators were losing more and more natural habitat to urbanization and infrastructure. They had to compete with agriculture for more and more shrinking territory limited to Japanese islands. Along with - same intentional as automatic - progress, Japanese wolf concept in Japanese folklore was replaced by its dangerous counterpart under the influence of Westernisation. However, between multiple shrines dedicated to multiple kami in Japan, still there are some typical wolf related. At Mitsumine in Chichibu, there is the most famous national one where wolf kami is still worshipped as a messenger or familiar spirit serving the local kami deity. In Higashiyoshino village (Nara Prefecture), on the Takami River bank, there's the Japanese wolf memorial - the wolf considered as the last one replica, inscribed with the haiku.

I walk

With that wolf

That is no more

A wild bear feeding next to fishermen who discharge salmons on the shore, wild deer herding nearby working farmers on the field like cows on the pasture, white-tailed eagles waiting for fish thrown to them by ice-fishing anglers. Documentary narrates about that intuitive cooperation as unprecedented phenomenon. Among them an old man is feeding red-crowned cranes - endangered species, local resident population, formerly counting 30. Nowadays, there are 1000 of Hokkaido, making their total population reach 3000 all over the world, on areas where they migrate.[6]

references:

Tresi Nonno; "On Ainu etymology of key concepts of Shintō: tamashii and kami" (2015)

Brett L. Walker, William Cronon; "The Lost Wolves Of Japan" (2009)

John Knight; "On the Extinction of the Japanese Wolf"; Asian Folklore Studies (1997)

[1] Pew Research Center results (2010)

[2] Geological evolution of Hokkaido, Japan: an example of collision orogenesis (1982); study by Hakuyu Okada (Institute of Geosciences, Shizuoka University, Japan)

[3] Reconstructing the colonization history of lost wolf lineages by the analysis of the mitochondrial genome (2014); research by collective work

[4] Phylogenetic Analysis of Extinct Wolves in Japan (2011); research by Ishiguro Naotaka (Gifu University Faculty of Applied Biological Sciences)

[5] Ancient DNA Analysis of the Oldest Canid Species from the Siberian Arctic and Genetic Contribution to the Domestic Dog (2015); research by collective work

[6] Wild Japan, BBC Asia documentary