Dreamcatcher's folk tradition vs fiction

Indian folk-art inspires independent artists, with myriad ideas of its realisations. Primary Oji-Cree twisted dual spiderweb design hung on the one loop where both net-knotted threads secured each other in their fulfilled role - a common hanging tool or a tiny necklace/amulet.

A few days ago I came back home after another macramé[1] workshop, with my own handcrafted "dreamcatcher" - a hoop equipped with a knotted web (for nightmares being caught) and string "feathers" (for them being evaporated when the sun rises). Tradition claims that it should be handmade, especially if dedicated individually to a chosen person.

It is said that at night, when dreams visit, they are caught in the dream catcher's web, and only the good dreams are able to find their way to the dreamer, filtering down through the feather. When the warmth of the morning sun arrives, it burns away the bad dreams that have been caught. The good dreams, now knowing the path, visit on other nights.

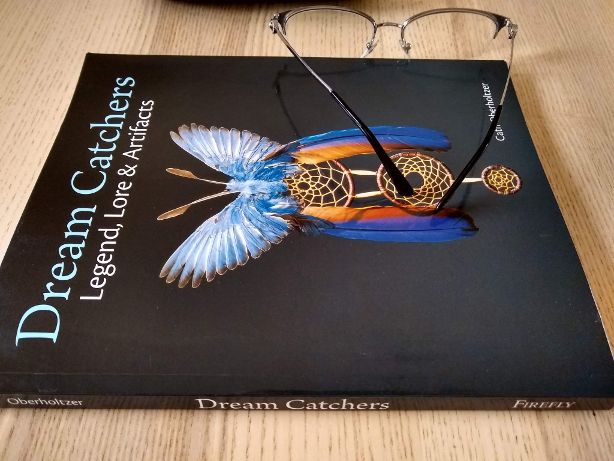

— Cath Oberholtzer[2] begins her illustrated book destined for open discussion about the ancient tool which metamorphosed by ages into a folk icon.

The confirmed dreamcatcher's origin points to Algonquins (Canada First Nations), where leading cultures are Ojibwa (Great Lakes region) and Cree (James Bay territory) - both enchaining me previously entwined into the Until Down game plot. They consider themselves connected into a community of persons, animal-persons and other-than-human persons - three-part world composed of Sky, Earth and Underworld populated by their ancestors, Grandfather Bear, thunderbirds, underwater panthers, horned snakes, little people, tricksters, spiders, animal keepers and the rest of spirits.

Dreamcatcher's functionality was defined by its creators, every time meaning the same

- a dreams' filter

Basic protector against bad spirits - not passing them inside a soul (nightmares, death) or passing them away (obsession, illness). Usually net charms dangled in front of the cradle, sometimes they were used as a barrier spread around the tepee. Inuit - non-Algonquian the First Nations culture - made dreamcatchers hanging in windows to not let negative forces get inside home.

Oji-Cree people believed in importance of filtered dreams as containing knowledge of future successful events.

- a visions' creator

Gate between the distant / alternative / opposite worlds - to communicate between a dreamed (dream visitor, spirit guide) and a dreamer experiencing the prediction.

Three circles of an optional dreamcatcher chain imagine past-present-future connection.

Aboriginal Ojibwe, Cree, Chippewa - Algonquian cultures - considered it as a device catching nightmares into a mesh-like web and letting good ones slip through the hole. Whereas, Indians of America (Sioux) spider fable narrates about catching good dreams and letting bad ones drip down the attached feathers; similar tales are shared by every tribe across North America as its own canon story.

Regular dreamcatcher was described in the book as willow twigs bent and fastened to form a hollow circle from two to four inches (5-10cm) in diameter filled with netting of sinew or nettle twine, typically in a pattern that mimicked the design of a spiderweb, originally without feathers included.

Spider thread is considered to connect the Sky World (spiritual reality) and the Earth World (physical reality) together. Primary Ojibwe twisted dual nettle fiber or fine yarn spiderweb design hung on the one loop where both net-knotted threads secured each other in their fulfilled role - a common hanging tool (Ojibwa) or a tiny necklace/amulet (Cree).

The man procures the wood and constructs the frames, the woman makes the netting and creates the protective design.

The author tries to explain the phenomenon of dreamcatcher being a mainstream icon

- European settlers in America -> history correlated to Indian reservations establishment

- Wild West 19th century -> indigenous folklore exhibited to Euro-Americans and transported across the ocean to Europe (i.e. Britain)

- 20th-century ethno-turism -> family autochthonic companions hadcrafting dreamcatchers by generation and passing tribal lore by parents to their children

- New Age (1960's) hobbystic re-creations referring to Eastern philosophy -> yin-yang zen (vide web arrangement) and crystals spiritual meaning (vide beaded stones).

Mongolian ritual artifact catalogued by the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of University of Cambridge (UK, 2004) as an "instrument for catching evil spirits" has feng-shui bells attached.

1990s computer technology boom and 21th-century internet expanse forced authenticity certificate obligatory for every manufactured dreamcatcher (avoiding mass-produced fakes).

Indian folk-art inspires independent artists, with myriad ideas of its realisations. Modern times dreamcatchers are equipped with braided beads or polished stones (New Age crystal healing related) which were introduced as spiritual booster. Stones' presence in Eurasian folklore would explain how and why glass beads appeared in dreamcatchers mass-made by North America Indians for gift shops or pow-wow kiosks, together with feathers, shells, tassels, wooden beads which complete them. Modern worlds' animal ethics and eco-trends became a prefect reason to use a natural cotton and wool as a sinew for net knotting.

Here we have reached the end of the story - my just workshopped dreamcatcher-inspired macramé.

It is neither the shape nor the materials used in contemporary dream catchers that are a critical factor. Rather, it is the spiritual power of the netting, constructed as it of lines and knots, and the owner's faith in that power which will prove to have lasting significance.

references/citations:

Cath Oberholtzer; "Dream Catchers: Legends, Lore & Artifacts" (2017, Canada)

[1] Art of knotting threads, cords, strings, straps, bonds, yarn and other suitable materials.

[2] Archaeologist and anthropologist; originally focused on the prehistory of southern Ontario (Canada), then shifted to cultural anthropology researching the early history of Crees (the James Bay area, Quebec).